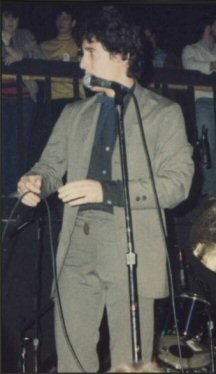

| People are turning

out for Wall of Voodoo on the strength of "Mexican

Radio," but what are they coming away with? Ridgway

isn’t sure. "I'm not very good at judging

how the band comes off," he explains. "I've

always looked at what we do as multileveled. Some of it

is completely absurd and some of it is seriously absurd.

A kid could like as much as someone older, but in a

different way. We're definitely not serious enough to be

considered an art band.

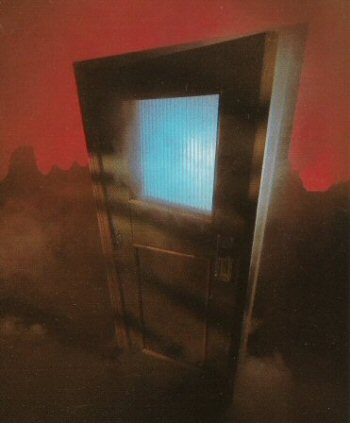

"The songs are

a bunch of little Twilight Zones strung together."

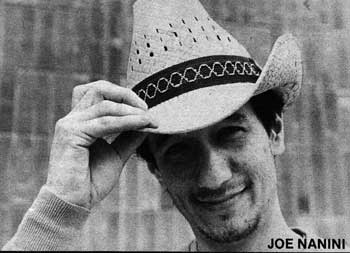

Although he denies

any significance, Stan Ridgway's earliest stab at show

business was with a Knucklehead ventriloquist's dummy at

age nine. Ventriloquism, you might say, was a

more primitive attempt at control than voodoo.

He grew up in Los

Angeles, in a house full of country-and-western music.

From there Ridgway got into blues, then jazz, then

classical. "I went to music school as a guitar

player and got totally burned out," he notes.

By the mid - '70s

he was committed to bebop. "Charlie Parker was my

hero. I wanted to be the Ornette Coleman of guitar. But

it got to the point where I didn't want to go in that

direction anymore; it had become a question of who's the

fastest gun. I wanted to simplify the structures of

'jazz-rock confusion music' and perhaps make songs out of

it."

Ridgway's

experiments circa 1976 foreshadowed much of what makes

Voodoo's music intriguing today. If he sounds like an

egghead, this explanation is really very simple:

"I started

working with rhythm machines because I wanted to alter

the ratio between rhythmic and harmonic elements. In most

songs the chords move along very evenly-dum, dum, dum-and

so do the drums. I was bored with that orthodox setup.

"I came across

the idea of making the rhythm go a different speed than

the chords. That sets up a relationship the listener can

enjoy whether he's aware of it or not. I wanted to get

away from the kind of music where people said, 'He sure

plays that diminished scale so groovy over that

chord!’ That's so pedantic."

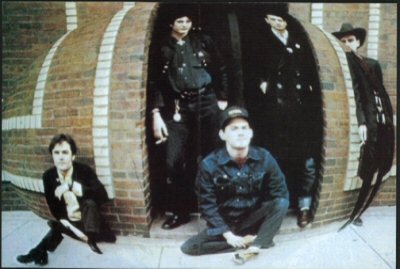

In 1977 Ridgway

formed a partnership with guitarist Marc Moreland, who

introduced him to the work of Kraftwerk, Eno and kindred

spirits. One thing that did not figure in his plans was

the rapidly spreading punk movement, which he describes

as "three chords, a cloud of dust, and a hearty

hi-yo Silver. I enjoyed the aggression, but.. .."

(His education is showing.)

|